The Judicial investigation about the double homicide of the journalists from El Espectador 1991 left aside other important hypothesis and ignored clues which were left written on a notebook. The presumed intellectual authors and crime materials were also murdered. There is no one sentenced by the case, which recently was admitted to the InterAmerican Commission of Human Rights.

SANDRA: I’m leaving, this is too scary.

I was one of her last words that Julio Daniel Chaparro hand wrote on his journalist notebook, before they killed him and the photographer Jorge Torres, on April 24th of 1991, in Segovia, a mining town on the northeast of the Colombian Antoquia. Who was Sandra? Why was she so scared? Her testimony has any connection with the El Espectador journalists’ death?

It’s been 30 years and there is still many questions, leaving without answers from the case, and many other reasons why the investigators did not follow clues left written by the journalist. It is known that the notebook existed because someone, at least, took precaution to photocopy three pages from it, before the Attorney destroyed it, along with the rest of his belongings. They were burnt for “being too dirty with blood and dirt” and they were “great health hazard”.

SEGOVIA, April 24-91

The title and date, framed between a drawn box with a pen, which can be read on the first pages from the photocopied notebook, which today make part of the judicial file. On this paper and the following, Chaparro left written (in cursive) what he shouldn´t forget about his journey: contacts names, calls to make, observations from the surroundings and a last verse.

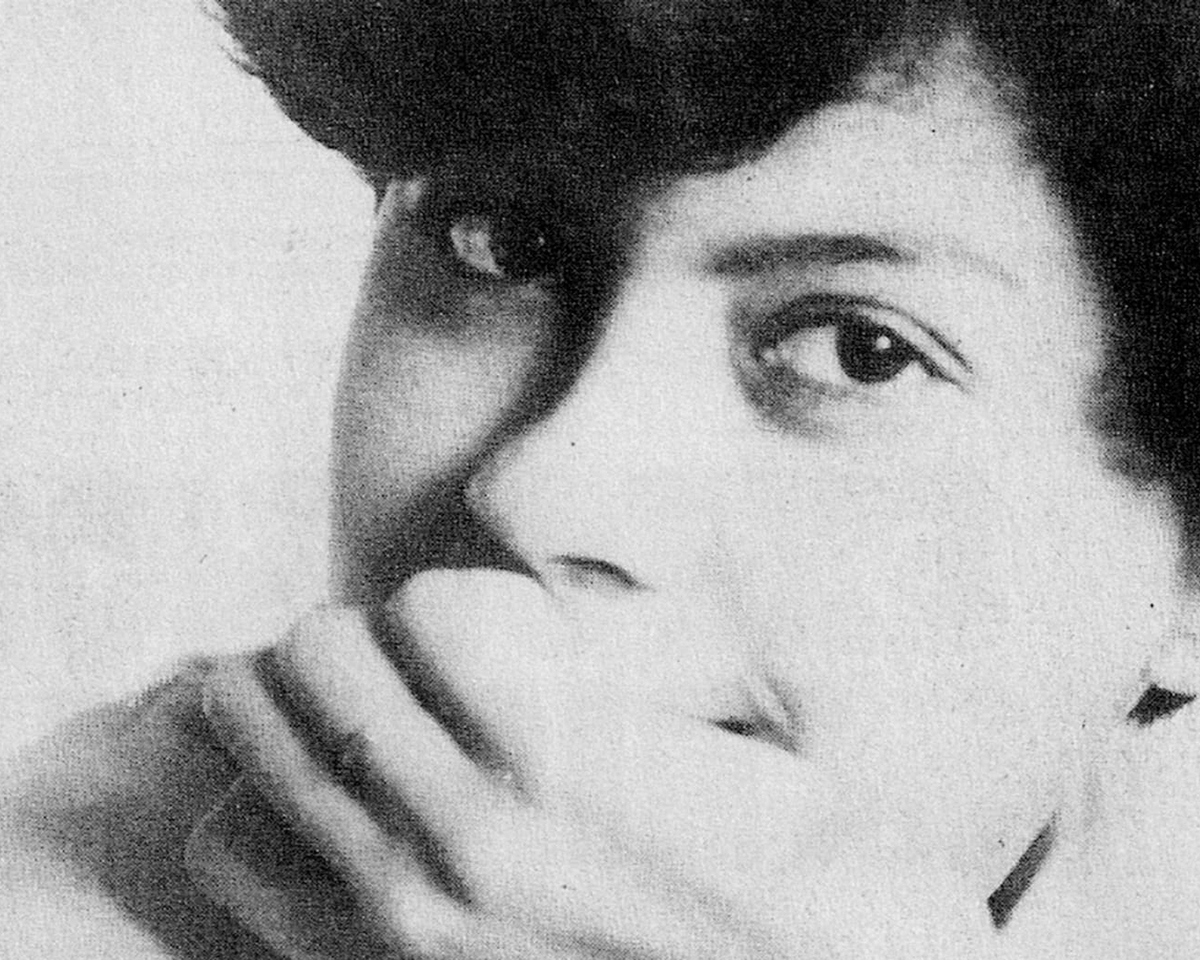

He had recently turned 29 years old, but he was a climbing star from the chronicles. Without any modesty, he assured that he would become the next Colombian Nobel of Literature. And when he wasn´t reporting, he wrote poetry. That double identity of a journalist-poet accompanied him everywhere. In the past months, he had dedicated himself to visit some of the districts mostly affected by war, to write a series of chronicles called “What violence took away”. The last one would be Segovia.

Tropical fragrance… hills, palms, oranges, potatoes, almonds

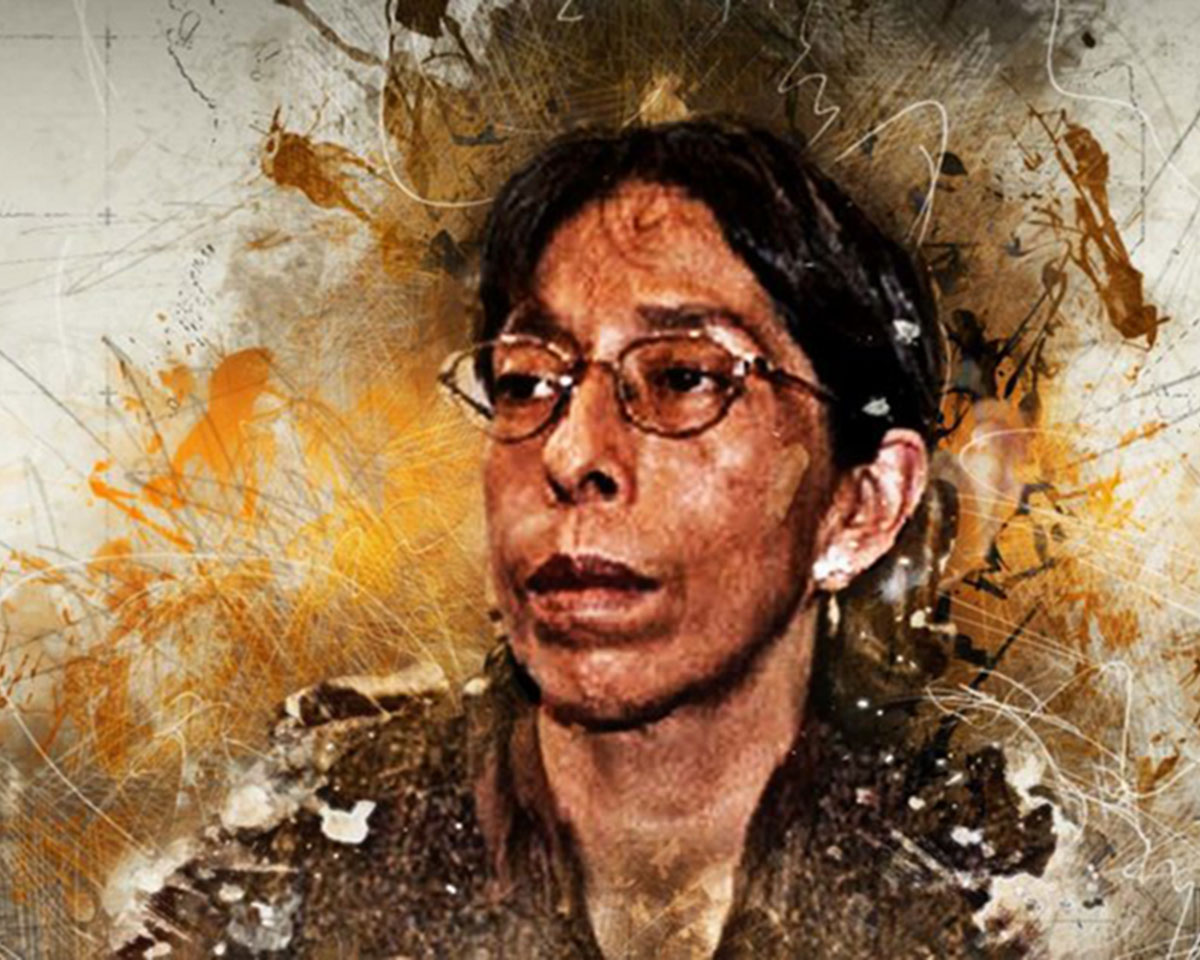

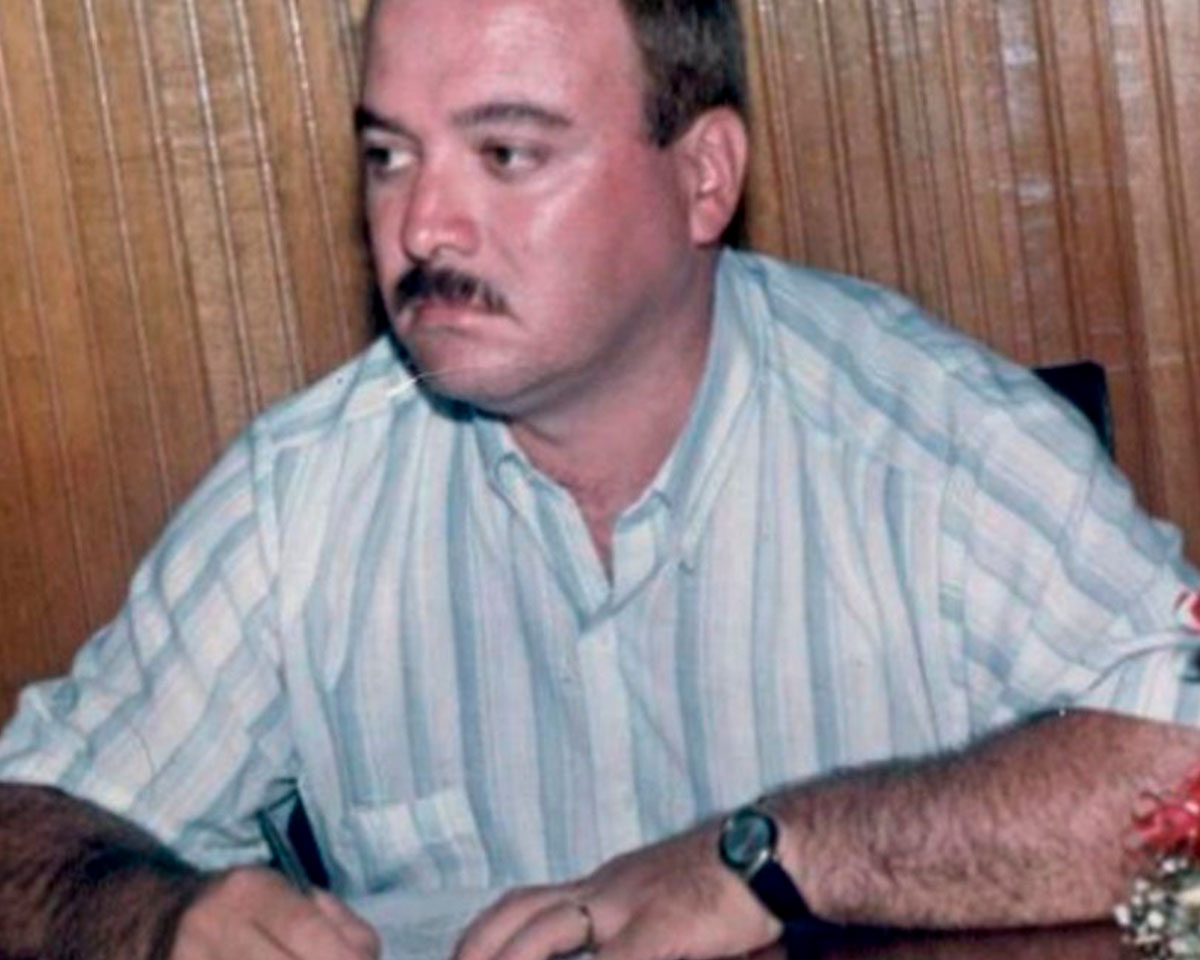

His traveling partner, Jorge Torres, had been added up at the last time, because the assigned photographer had gone sick. Although Segovia was a difficult, Torres took his place with no forecast. He had more than 20 years of experience and he was present on attacks, the kidnapping from an embassy and raids from several armed groups. His speed to change rolls was legendary; he would’ve permitted to save the only portrait from a guerrilla intake in Caqueta, before a soldier took his camera.

On that Wednesday in the morning, before parting, Chaparro went to say goodbye to two of his children’s school and Torres assured his wife that he would come back the next day, to help her with the last arrangements from the quinceanera party for his daughter Diana, that would be held on Saturday. Midafternoon, they flew to Bogota to Medellin to the next district, Remedios. On landing, a soldier from the Platoon Bombona asked them to identify themselves and both did it as they were journalists from El Espectador, in the list of passengers’ movements, right before continuing for the highway to their final destiny. Arriving to Segovia they registered in the Fujiyama, they left their suitcases, and after calling someone from the phone in reception, they went out to the streets from that town, which distrusted from any tourist after that Friday, November 11th of 1988.

Mayor Rita Ivonne Tobón

The Mayor Rita reached to see when a convoy of trucks with armed men, dressed and armed like Rambo, from the paramilitary Death to the Revolutionaries from the Northeast (MRN), entered the other side of the road burst shooting to everything that moved in town. They went up the street La Reina and, the list in hand, they murdered every supporter and collaborator from the new left-wing party, Patriotic Union, (the mayor Rita, saved herself because she hid) and anyone which was a guerrillero member: the Colombian Revolutionary Armed Forces (FARC) or the National Liberation Army (ELN).

More than 40 people were murdered and other fifty ended up wounded, without the Police nor the Army, made anything to stop the massacre. Since then, Segovia’s habitants trusted less on the Public forces and sympathized more with the Guerrillera Coordinator Simon Bolivar, which grouped many Army rebels.

CGSB orders- 1st Commanders meeting

Chaparro took notes from the paintings there were on the walls.

Miners climbed at 5

They saw Torres taking pictures in the cemetery, the main square, the monument to Maria and the park.

Palomares... Gathering Park

It was in the park, near to the monument to the Mine, which the journalists found patrols from the Antiguerrilla police. One of them felt nervous to see them, overall for the cameras. Chaparro and Torres told them they were tourists, not reporters, and the agent never asked them for an ID. They spoke for a couple of minutes and they must have asked about the Public Order, because Chaparro wrote after:

Until 15 days ago. OK. Now they disturbed the neighborhood ahead and there are deaths-Agent.

Reporters continued to the La Reina and entered a tavern which had the same name from Torres’ daughter.

Estadero Diana

They were the only clients. They sat at the bar, drank a pair of beers and they met Alexandra, mostly known as Sandra or Aleida. She posed for the camera and wrote a phone number from a house in Medellin where they could send the pictures later. While they were still there, reporters asked them to play again and again a catchy song by Francis Cabrel.

I want her till death, I want her till death, and I want her to death…

Years later. Alexandra-Sandra-Aleida would tell the investigators which interrogated her that the journalists have asked what was beyond that town and they indicated there was a gorge.

La Cianurada.

Before 7pm, they cashed the order of three thousand pesos and they left the place. Who were they going to meet? Was it the person they called before going out of the hotel? Did that person live, in fact, on the La Reina Street? Was he a survivor of a massacre? Was the other one Sandra, Sandra Lezcano, as it appears on a page before from the notebook? Were they going to La Cianurada?

The last phrase, or last verse, was that the chronist-poet left on his notebook:

Take a peep at the white sun of April

Seconds, minutes, immediate hours after a murder are the most valuable. If the investigators do not act with the expertise and diligence necessary, within that close range of time, it is more difficult to find the responsible.

The military William Silva received an anonymous call at 19:40. He was informed that in La Reina they have killed two men. How much time passed since the call to the station and the moment on which the police got the crime scene? Nobody knows. Some say it was half an hour, one or two. Agents claimed they had to wait for a group from the Army to get on that street, where armed people used to live, because it could be a trap. In any case, they got there late.

And they did not tell the instruction 30 Segovia judges, Nubia Jaramillo, with whom belonged to lift the corpses, but they did it by themselves. On the jury’s absence, the police used two citizens, as witnesses, on the lifting of corpses. On their report the only objects found next to the bodies, laid upside down and their hands tied, it was the glasses aviator style from Chaparro and his last box of Royal cigarettes. The two cameras from Torres never appeared, but one of the witnesses was threatened by a man, days later, to change her declaration and say that they had found the photographic material.

Neither was any gun vanilla left on the floor, according to the report. As of from one bullet found on Torres’ body, Legal Medicine determined that the shots came from a revolver38.The gunmen knew what they were doing: they just aimed at the heads.

Who shot them? That night, out of fear, ineptitude or lack of experience, none of the police officers who were at the crime scene collected a single clue, among the neighbors and potential witnesses. Police officer Johnson Sosa said the following in regard: "As is well known, people from this municipality keep total secrecy with members of the public force and do not collaborate with them at all." But as a judge who reviewed the proceedings and the evidence that had been put on eight months after the murder of the reporters concluded to no avail: "expertise was needed and indigenous malice lacked in interviewing the witnesses."

That is why it was so convenient that two alleged witnesses to the crime appeared in early November 1991. They had been detained at a military checkpoint. Who offered to collaborate in exchange for protection and a job as Army informants. They said journalists had been mistaken for government intelligence agents and ordered to abduct them. Then they decided that it would be "better to kill them than to make those bastards fat in the mountains."

The hypothesis that the urban militiamen (first they said they were from the FARC, and then they were from the ELN) had killed them by mistake would be reinforced by statements from some people, such as the mayor of Segovia: “People are stressed and look at the answer. People fear the stranger as a result of the massacre of 88 and have not been able to forget.

Other hypotheses, among them that they had been murdered by members of the public force, or by some paramilitary group for the type of journalistic work that Julio Daniel Chaparro did (in a previous article on the Voladores massacre he had written that those responsible were Fidel's men Castaño, who had also perpetrated the '88 massacre in Segovia, in alliance with a liberal political cacique) were discarded, or rather never investigated.

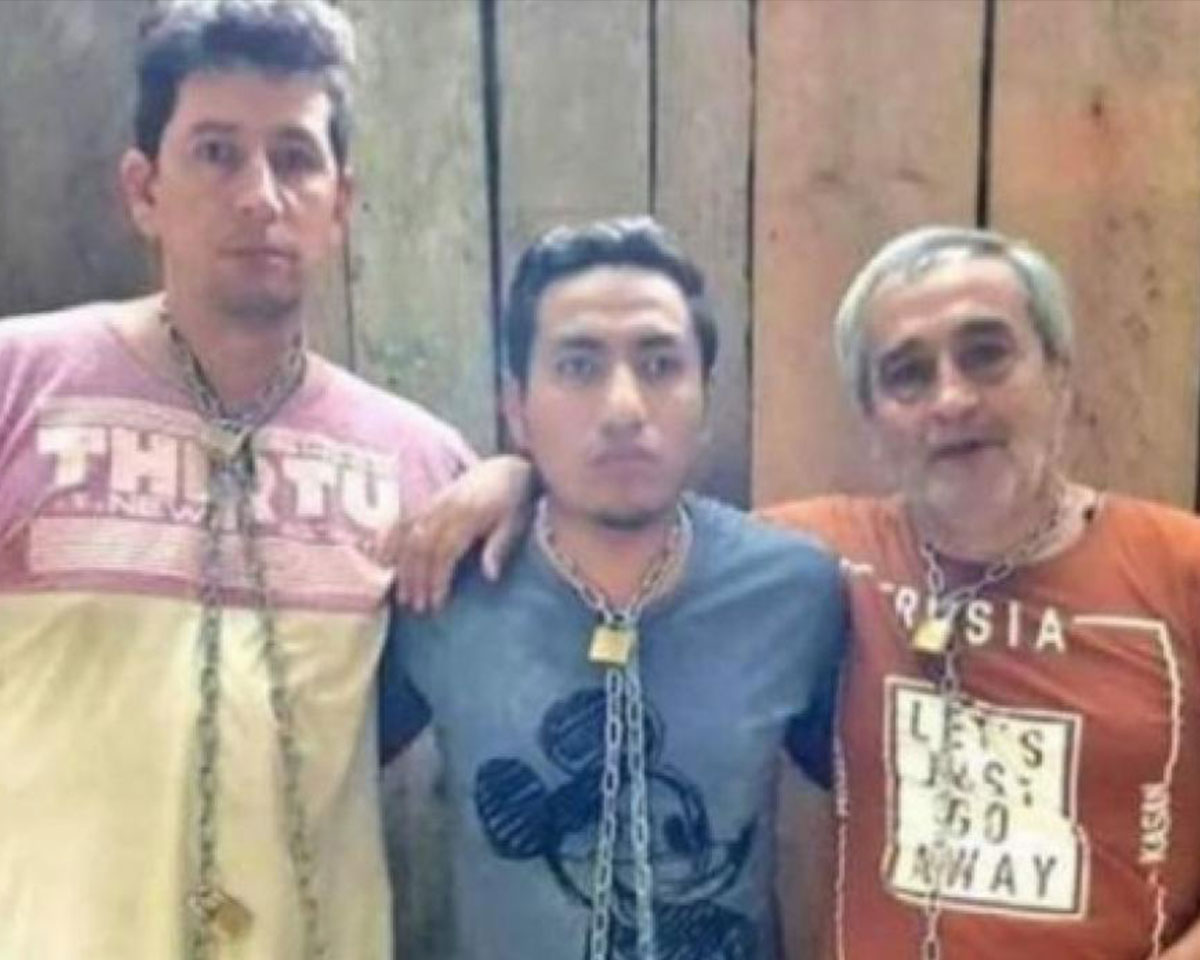

The only ones arrested for the crime were the Ramiro brothers and Joaquín Lezcano, who according to the informants had been the intellectual authors of the crime. But after three years they were released because it was never proven that they were members of the guerrilla and had given the instructions to others to execute it. When another unit of the Prosecutor's Office reactivated the investigation, years later, and returned looking for them, and the alleged material authors, all had been murdered. Joaquin’s daughter, Sandra Lezcano, would be questioned, but she was never asked if she had met the journalists or why her name appeared on one of the pages of Chaparro's notebook.

Other procedural failures, negligence or unjustifiable delays are observed in the file: there are illegible pages, handwritten by some of the defendants, which no one bothered to transcribe; the case was lost or “misplaced” in another agency for almost a year; they allowed a lot of time to search for additional evidence or proceedings.

"What is not being investigated here, for me, is the murder of two journalists," says Daniel Chaparro, eldest son of the murdered reporter, who has insisted that the murder of his father - and also his journalistic and poetic work - not remain in oblivion. For this reason, in April 2011, when 20 years had already passed, the families of Julio Daniel Chaparro and Jorge Torres asked to declare the crime against humanity. The Prosecutor's Office rejected the petition because it considered that "it was an isolated and spontaneous, unplanned, directed and organized event, carried out because of the activity that these communicators carried out anonymously, before the eyes of the people."

Later, in 2018, the Prosecutor's Office declared it an imprescriptible “war crime”, and decided to bind and accuse the entire Central Command of the ELN for the crimes of aggravated homicide. Once again, in his accusation, he maintained the original hypothesis that they had been killed by mistake and not because they were journalists, since their identity was only known after their death. The case is in trial stage and on June 30, 2021, the first hearing was held before a judge.

In parallel, the families of Chaparro and Torres, FLIP, and the Inter-American Press Association (IAPA) presented the case before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. On July 28th, 2021, the Commission declared the case admissible. Regardless of what happens with the case at the IACHR and with the trial in Colombia, families do not have much hope that truth will be known, after so long. "Leave it as it is“, says Diana Torres, the photographer’s daughter,” not knowing what really happened, it is what we have questioned so much, because that is part of impunity."